Bamana seated female figure

Bamana peoples

Mali

Early to mid-20th century

H. 89 cm

Provenance :

Pierre Vérité (1900-1993), Paris, 1954.

Franco Monti, italian modernist sculptor (1931-2008), Milano.

Albert Galaverni (1933-2013), Parma.

Note of Alberto Galaverni in is art inventory regarding this figure : “Bamana, Mali. A seated female figure. Unusual representation of a woman, probably the wife of an important chief as represented sitting on a high chair, a symbol of power. Carved in hard wood, fire incision from a decorative pattern reproducing the traditional scarifications. Ex-collection P. Verite, Paris, 1954”

Publication :

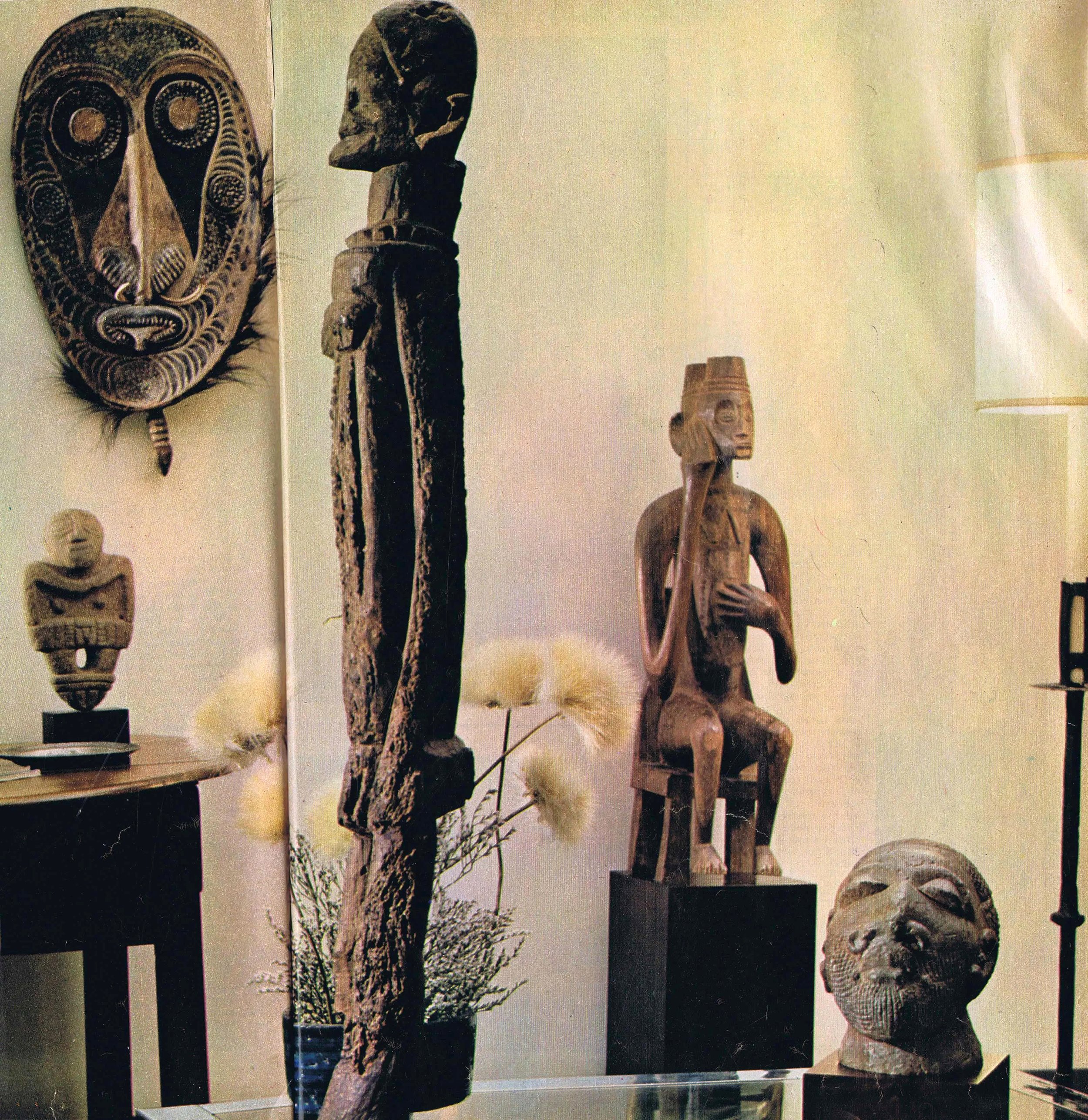

In Panorama N°35, Milano, 1965 - For Franco Monti’s interview about his art collection.

In Bamana society, individuals can acquire mystical knowledge through initiation into a number of distinct associations. Induction into the Jo association followed a six-year course of study by all young men and some women. Jo’s leadership sponsored the creation of sculptures by Bamana blacksmiths that represented cultural ideals and values. The regal protagonists are defined by a crisp precision and idealized naturalism that exemplifies jayan, or aesthetic of clarity. The visual impact of the larger-than-life allegorical figures attracted the attention, focused the eye, and directed the thoughts of viewers who assembled to reflect collectively upon shared social ideals.

Figures like these appear in the annual celebrations of Jo, an association of initiated men and women living in southern Mali. They also appear in the rituals of Gwan, a related institution concerned with helping women to conceive and bear healthy children. Jo and Gwan sculptures are larger than most Bamana figures, and their distinctive style consists of massive, rounded forms rather than the angular, cubistic ones more typical of Bamana art. Finely incised scarification marks cover their faces, necks, and torsos.

For annual Jo and Gwan rituals, the sculptures are removed from their shrines, cleaned and oiled, decorated with cloth and beads, and set up in the village square in groups. The groupings always feature a mother and child, usually accompanied by a similarly attired male figure and several other male and female figures. The mother and child and her male counterpart are seated in positions of honor, wearing and holding tokens of their physical and supernatural powers - among them, knives, lances, and amulet-studded hats. The companion figures are often shown in attitudes of respect and submission. When viewed as a whole, these groups of sculptures are the embodiment of Bamana ideals and behavior.

Although sculptures such as these continue to be produced and displayed in a few Bamana villages, some may have been made considerably earlier. Many of the ornaments and weapons seen on the Jo and Gwan figures are also found on terracotta figures from Mali that date from the twelfth to the seventeenth century.

Hairstyles vary but usually exhibit some variation on a crestlike arrangement—this figure's coiffure consists of three horizontal crests. The aesthetic beauty of such works is heightened by the addition of beads or metal accessories and oil, which is rubbed into the figure to produce a lustrous surface. These additions are comparable to the manner in which young Bamana women prepare themselves for special occasions. The incised patterns on the torso of the figure correspond to scarification marks once made to beautify adolescent Bamana women.

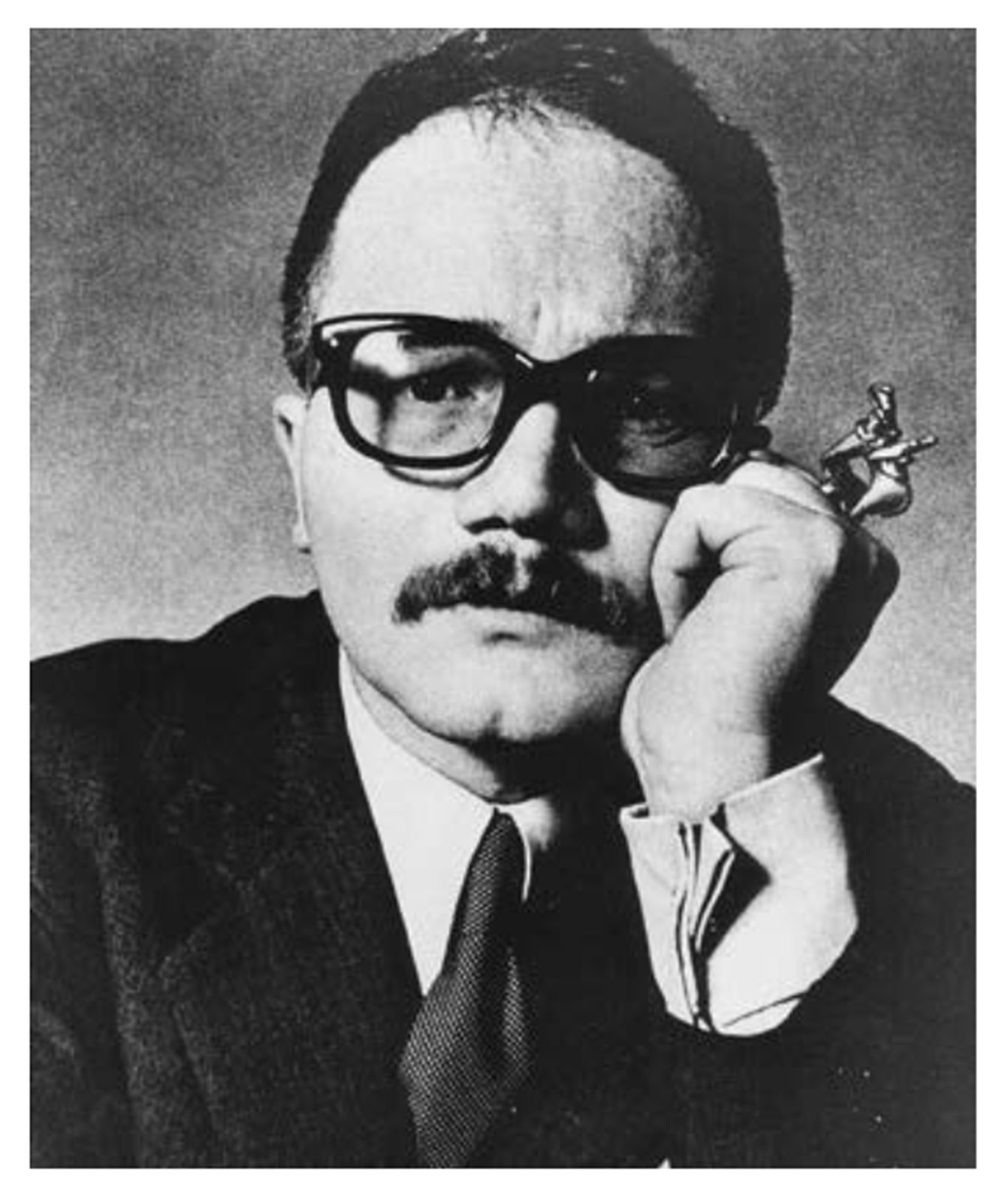

About Franco Monti’s Collection

Franco Monti was born in Milan in 1931. From an early age he was interested in the arts, particularly sculpture and in the early 50’s he began modeling clay and carving stone anthropomorphic figures. He became engaged in the French school of ethnology and his interest in African art would give him a new perspective on sculpture, and became his inspiration for his extensive travels to West Sub-Saharan Africa.

The objects were collected in situ with great understanding and respect for the cultures he visited. Many of the objects that he found in the field, can now be found in museums and collections all over the work. The famous Baule mask of the Totokro master was found by him in situ. Back in Europe, he promoted initiatives and organized exhibitions to divulge the non European arts in Italy and abroad.

Fully integrated into the cultural world of the ’60s, he becomes friends with the most important representatives of culture in Italy with artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Marino Marini, Fontana, De Chirico, Morandi, Mario Negri, and other influential characters in the art word like Peggy Guggenheim, John Huston and Eugene Bermann, designer of the Met Opera House and La Scala.

At the same time, he worked in Paris. Together with his dear friend and colleague, Charles Ratton, he became a member of the Syndicat Français des Experts en Œuvres d’ Art de Paris, and is considered an expert on African sculpture to which he has dedicated over 30 years of field research. He collaborates as an expert for “primitive arts” publications of the publishers Fabbri and De Agostini. In Italy he wrote for “Corriere della Sera” the renowned art Revue. With his in-depth knowledge of primitive arts, the Mondadori magazine “Panorama” interviews him in August 1965 about his experience in Africa, and contact with those cultures (the object we are presenting is published in this edition - see picture above).

In 1967 the Civic Museum – the Kunsthalle – of the city of Darmstadt (Germany) organized a retrospective exhibition of his African art collection.

In 1971 he oversees the section of Non-European arts in the exhibition “Il Cavaliere Azzurro” (Der Blaue Reiter) at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna di Torino and in 1979 coordinates the same section of “Origini dell ‘Astrattismo” the most important and extensive exhibition on the subject ever held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan.

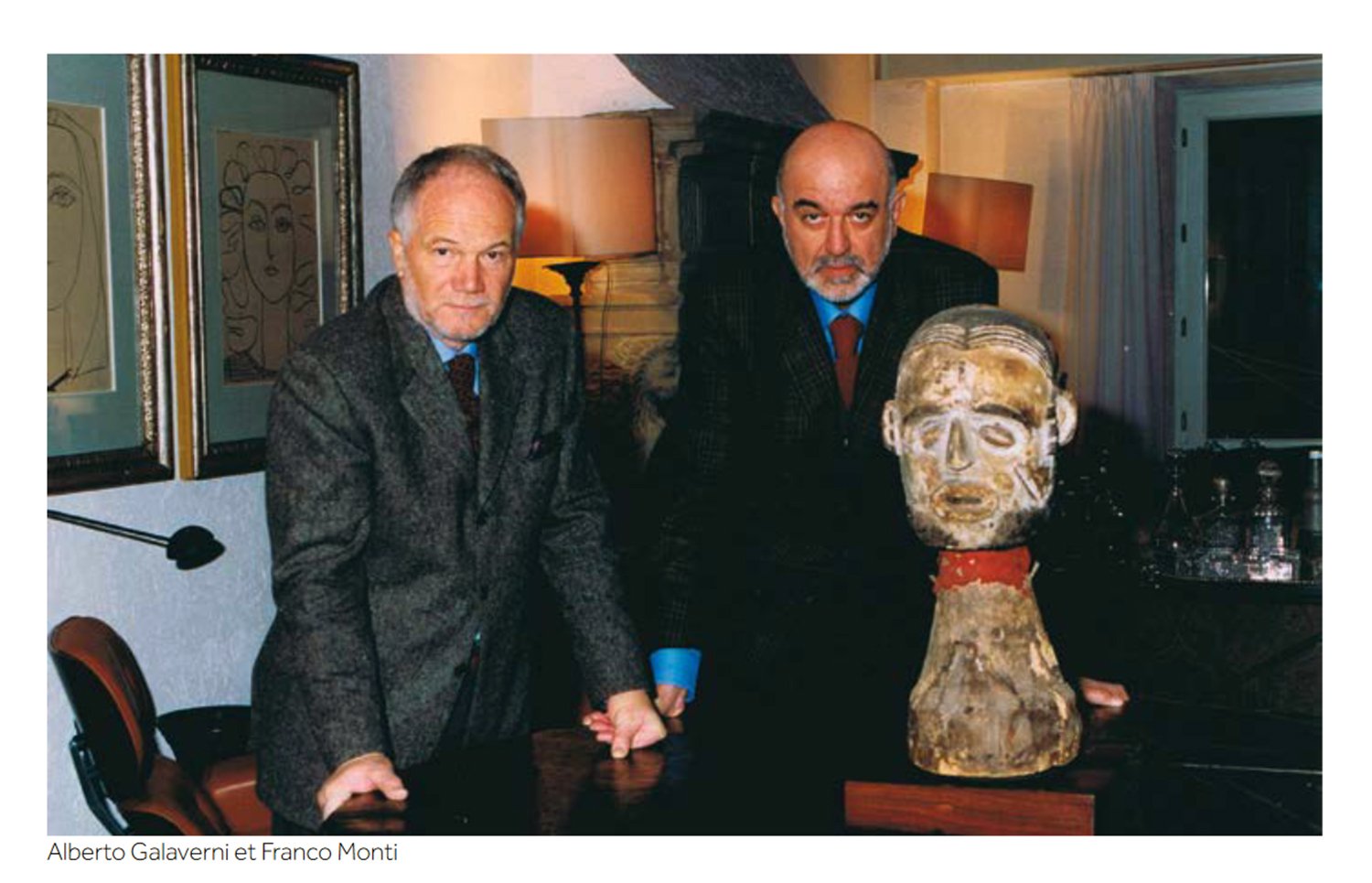

About Alberto Galaverni

Alberto was a friend of Luchino Visconti and Michelangelo Antonioni. He worked with renowned British and American museum directors. Before that, he met great masters like Pablo Picasso or Henry Moore thanks to his privileged relationship with Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the historian and promoter of Cubism, who gave him a portrait of himself by Picasso in 1972.

In the 1960’s Galaverni discovers a new interest for the African arts, major expression of the extra-european arts . In Milan, he met Franco Monti, it is thanks to the latter that he made the acquaintance of Raffaele Carrieri, Luigi Carluccio and the collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo. And in Paris, he met Michel Leiris and Pierre Restany.

Bamana peoples

Mali

Early to mid-20th century

H. 89 cm

Provenance :

Pierre Vérité (1900-1993), Paris, 1954.

Franco Monti, italian modernist sculptor (1931-2008), Milano.

Albert Galaverni (1933-2013), Parma.

Note of Alberto Galaverni in is art inventory regarding this figure : “Bamana, Mali. A seated female figure. Unusual representation of a woman, probably the wife of an important chief as represented sitting on a high chair, a symbol of power. Carved in hard wood, fire incision from a decorative pattern reproducing the traditional scarifications. Ex-collection P. Verite, Paris, 1954”

Publication :

In Panorama N°35, Milano, 1965 - For Franco Monti’s interview about his art collection.

In Bamana society, individuals can acquire mystical knowledge through initiation into a number of distinct associations. Induction into the Jo association followed a six-year course of study by all young men and some women. Jo’s leadership sponsored the creation of sculptures by Bamana blacksmiths that represented cultural ideals and values. The regal protagonists are defined by a crisp precision and idealized naturalism that exemplifies jayan, or aesthetic of clarity. The visual impact of the larger-than-life allegorical figures attracted the attention, focused the eye, and directed the thoughts of viewers who assembled to reflect collectively upon shared social ideals.

Figures like these appear in the annual celebrations of Jo, an association of initiated men and women living in southern Mali. They also appear in the rituals of Gwan, a related institution concerned with helping women to conceive and bear healthy children. Jo and Gwan sculptures are larger than most Bamana figures, and their distinctive style consists of massive, rounded forms rather than the angular, cubistic ones more typical of Bamana art. Finely incised scarification marks cover their faces, necks, and torsos.

For annual Jo and Gwan rituals, the sculptures are removed from their shrines, cleaned and oiled, decorated with cloth and beads, and set up in the village square in groups. The groupings always feature a mother and child, usually accompanied by a similarly attired male figure and several other male and female figures. The mother and child and her male counterpart are seated in positions of honor, wearing and holding tokens of their physical and supernatural powers - among them, knives, lances, and amulet-studded hats. The companion figures are often shown in attitudes of respect and submission. When viewed as a whole, these groups of sculptures are the embodiment of Bamana ideals and behavior.

Although sculptures such as these continue to be produced and displayed in a few Bamana villages, some may have been made considerably earlier. Many of the ornaments and weapons seen on the Jo and Gwan figures are also found on terracotta figures from Mali that date from the twelfth to the seventeenth century.

Hairstyles vary but usually exhibit some variation on a crestlike arrangement—this figure's coiffure consists of three horizontal crests. The aesthetic beauty of such works is heightened by the addition of beads or metal accessories and oil, which is rubbed into the figure to produce a lustrous surface. These additions are comparable to the manner in which young Bamana women prepare themselves for special occasions. The incised patterns on the torso of the figure correspond to scarification marks once made to beautify adolescent Bamana women.

About Franco Monti’s Collection

Franco Monti was born in Milan in 1931. From an early age he was interested in the arts, particularly sculpture and in the early 50’s he began modeling clay and carving stone anthropomorphic figures. He became engaged in the French school of ethnology and his interest in African art would give him a new perspective on sculpture, and became his inspiration for his extensive travels to West Sub-Saharan Africa.

The objects were collected in situ with great understanding and respect for the cultures he visited. Many of the objects that he found in the field, can now be found in museums and collections all over the work. The famous Baule mask of the Totokro master was found by him in situ. Back in Europe, he promoted initiatives and organized exhibitions to divulge the non European arts in Italy and abroad.

Fully integrated into the cultural world of the ’60s, he becomes friends with the most important representatives of culture in Italy with artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Marino Marini, Fontana, De Chirico, Morandi, Mario Negri, and other influential characters in the art word like Peggy Guggenheim, John Huston and Eugene Bermann, designer of the Met Opera House and La Scala.

At the same time, he worked in Paris. Together with his dear friend and colleague, Charles Ratton, he became a member of the Syndicat Français des Experts en Œuvres d’ Art de Paris, and is considered an expert on African sculpture to which he has dedicated over 30 years of field research. He collaborates as an expert for “primitive arts” publications of the publishers Fabbri and De Agostini. In Italy he wrote for “Corriere della Sera” the renowned art Revue. With his in-depth knowledge of primitive arts, the Mondadori magazine “Panorama” interviews him in August 1965 about his experience in Africa, and contact with those cultures (the object we are presenting is published in this edition - see picture above).

In 1967 the Civic Museum – the Kunsthalle – of the city of Darmstadt (Germany) organized a retrospective exhibition of his African art collection.

In 1971 he oversees the section of Non-European arts in the exhibition “Il Cavaliere Azzurro” (Der Blaue Reiter) at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna di Torino and in 1979 coordinates the same section of “Origini dell ‘Astrattismo” the most important and extensive exhibition on the subject ever held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan.

About Alberto Galaverni

Alberto was a friend of Luchino Visconti and Michelangelo Antonioni. He worked with renowned British and American museum directors. Before that, he met great masters like Pablo Picasso or Henry Moore thanks to his privileged relationship with Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the historian and promoter of Cubism, who gave him a portrait of himself by Picasso in 1972.

In the 1960’s Galaverni discovers a new interest for the African arts, major expression of the extra-european arts . In Milan, he met Franco Monti, it is thanks to the latter that he made the acquaintance of Raffaele Carrieri, Luigi Carluccio and the collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo. And in Paris, he met Michel Leiris and Pierre Restany.

Bamana peoples

Mali

Early to mid-20th century

H. 89 cm

Provenance :

Pierre Vérité (1900-1993), Paris, 1954.

Franco Monti, italian modernist sculptor (1931-2008), Milano.

Albert Galaverni (1933-2013), Parma.

Note of Alberto Galaverni in is art inventory regarding this figure : “Bamana, Mali. A seated female figure. Unusual representation of a woman, probably the wife of an important chief as represented sitting on a high chair, a symbol of power. Carved in hard wood, fire incision from a decorative pattern reproducing the traditional scarifications. Ex-collection P. Verite, Paris, 1954”

Publication :

In Panorama N°35, Milano, 1965 - For Franco Monti’s interview about his art collection.

In Bamana society, individuals can acquire mystical knowledge through initiation into a number of distinct associations. Induction into the Jo association followed a six-year course of study by all young men and some women. Jo’s leadership sponsored the creation of sculptures by Bamana blacksmiths that represented cultural ideals and values. The regal protagonists are defined by a crisp precision and idealized naturalism that exemplifies jayan, or aesthetic of clarity. The visual impact of the larger-than-life allegorical figures attracted the attention, focused the eye, and directed the thoughts of viewers who assembled to reflect collectively upon shared social ideals.

Figures like these appear in the annual celebrations of Jo, an association of initiated men and women living in southern Mali. They also appear in the rituals of Gwan, a related institution concerned with helping women to conceive and bear healthy children. Jo and Gwan sculptures are larger than most Bamana figures, and their distinctive style consists of massive, rounded forms rather than the angular, cubistic ones more typical of Bamana art. Finely incised scarification marks cover their faces, necks, and torsos.

For annual Jo and Gwan rituals, the sculptures are removed from their shrines, cleaned and oiled, decorated with cloth and beads, and set up in the village square in groups. The groupings always feature a mother and child, usually accompanied by a similarly attired male figure and several other male and female figures. The mother and child and her male counterpart are seated in positions of honor, wearing and holding tokens of their physical and supernatural powers - among them, knives, lances, and amulet-studded hats. The companion figures are often shown in attitudes of respect and submission. When viewed as a whole, these groups of sculptures are the embodiment of Bamana ideals and behavior.

Although sculptures such as these continue to be produced and displayed in a few Bamana villages, some may have been made considerably earlier. Many of the ornaments and weapons seen on the Jo and Gwan figures are also found on terracotta figures from Mali that date from the twelfth to the seventeenth century.

Hairstyles vary but usually exhibit some variation on a crestlike arrangement—this figure's coiffure consists of three horizontal crests. The aesthetic beauty of such works is heightened by the addition of beads or metal accessories and oil, which is rubbed into the figure to produce a lustrous surface. These additions are comparable to the manner in which young Bamana women prepare themselves for special occasions. The incised patterns on the torso of the figure correspond to scarification marks once made to beautify adolescent Bamana women.

About Franco Monti’s Collection

Franco Monti was born in Milan in 1931. From an early age he was interested in the arts, particularly sculpture and in the early 50’s he began modeling clay and carving stone anthropomorphic figures. He became engaged in the French school of ethnology and his interest in African art would give him a new perspective on sculpture, and became his inspiration for his extensive travels to West Sub-Saharan Africa.

The objects were collected in situ with great understanding and respect for the cultures he visited. Many of the objects that he found in the field, can now be found in museums and collections all over the work. The famous Baule mask of the Totokro master was found by him in situ. Back in Europe, he promoted initiatives and organized exhibitions to divulge the non European arts in Italy and abroad.

Fully integrated into the cultural world of the ’60s, he becomes friends with the most important representatives of culture in Italy with artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Marino Marini, Fontana, De Chirico, Morandi, Mario Negri, and other influential characters in the art word like Peggy Guggenheim, John Huston and Eugene Bermann, designer of the Met Opera House and La Scala.

At the same time, he worked in Paris. Together with his dear friend and colleague, Charles Ratton, he became a member of the Syndicat Français des Experts en Œuvres d’ Art de Paris, and is considered an expert on African sculpture to which he has dedicated over 30 years of field research. He collaborates as an expert for “primitive arts” publications of the publishers Fabbri and De Agostini. In Italy he wrote for “Corriere della Sera” the renowned art Revue. With his in-depth knowledge of primitive arts, the Mondadori magazine “Panorama” interviews him in August 1965 about his experience in Africa, and contact with those cultures (the object we are presenting is published in this edition - see picture above).

In 1967 the Civic Museum – the Kunsthalle – of the city of Darmstadt (Germany) organized a retrospective exhibition of his African art collection.

In 1971 he oversees the section of Non-European arts in the exhibition “Il Cavaliere Azzurro” (Der Blaue Reiter) at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna di Torino and in 1979 coordinates the same section of “Origini dell ‘Astrattismo” the most important and extensive exhibition on the subject ever held at the Palazzo Reale in Milan.

About Alberto Galaverni

Alberto was a friend of Luchino Visconti and Michelangelo Antonioni. He worked with renowned British and American museum directors. Before that, he met great masters like Pablo Picasso or Henry Moore thanks to his privileged relationship with Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the historian and promoter of Cubism, who gave him a portrait of himself by Picasso in 1972.

In the 1960’s Galaverni discovers a new interest for the African arts, major expression of the extra-european arts . In Milan, he met Franco Monti, it is thanks to the latter that he made the acquaintance of Raffaele Carrieri, Luigi Carluccio and the collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo. And in Paris, he met Michel Leiris and Pierre Restany.